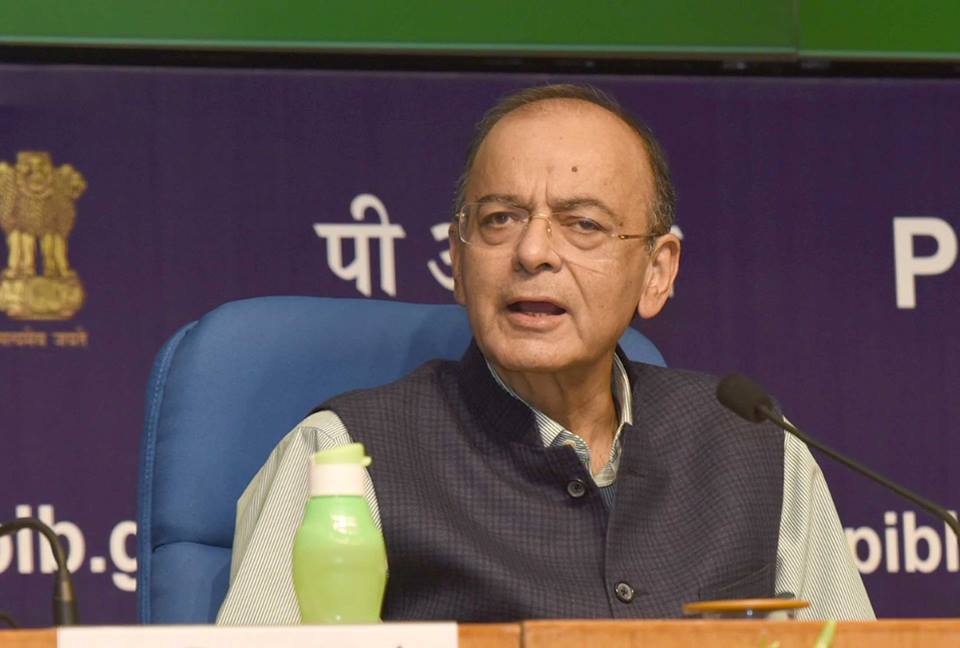

Why Agriculture, Rural Development and Healthcare Require a GST Council Type Structure? – Arun Jaitley

The GST was enabled by a Constitution Amendment which was unanimously approved by both the Houses of Parliament. Several legislations to implement the GST were passed by the Parliament. Laws relating to the State GST (SGST) were approved by all the State Legislatures.

The GST has enabled a single indirect tax in the whole country. Its implementation, compared to several other countries in the world, has been extremely smooth. Some initial teething trouble are to be expected. Everyone learns from experience. Not only did the GST consolidate multiple taxes and multiple cesses, it eliminated barriers in the country overnight. The whole of the country became a single market. Inspectors were eliminated; taxes were reduced and interface between the assesse and the Department was reduced. The online filing of returns and assessment was the order of the day. The input tax credit prevented the cascading effect of tax on tax and ensured that the back chain in manufacturing and services was done through authorisedly. A more efficient system detected leakages and improved the revenue collections. States have been guaranteed, for the first five years, a 14 per cent increase in annual revenue. For the first time since Independence, consumers have witnessed a continuous reduction of taxes.

https://www.facebook.com/ArunJaitley/videos/525395324654555/

The decision making process of the Council

Chairing the Council in its initial years has been one of my most satisfying experiences. The quality of participation of State Finance Ministers and their supporting Civil Servants was extremely high. The debates in the Council were on issues of substance. There was no populism. Concern for revenue, consumers, industry and trade dominated the discourse. They concentrated on simplifying procedures. Members shed their political colours outside the meeting venue. To satisfy their political constituencies, some spoke outside the meeting but inside there was an atmosphere of positive suggestions. At times conflicting views and thereafter the consensus.

Thousands of decisions have been taken in the Council. These range from framing of new regulations, circulars, notifications and tariff fixation. Council was always prepared, based on market reports, to make changes wherever required.

The States effectively had a two-third voting right and the Central Government had one-third voting right. All decisions had to be approved by at least three-fourth majority. This necessarily meant that the Centre and the States had to work together. Yet the Council set an incredible precedent which recognises the delicate balance of India’s federalism by taking all decisions through consensus and not once putting any decision to vote. I hope this continues in future. The decision making culture involved extensive discussions flagging various viewpoints and, thereafter, formulating the consensus. A consensus is never imposed, it evolves. Where consensus was not possible, the matter was not pursued.

The lessons from the GST Council

The GST Council has become India’s first federal institution. Its working is a role model in other areas where federal institutions are needed in India. It displays the maturity of India’s democracy and politics. When larger national interest requires, decision makers can rise to the occasion. It negates the popular impression that politicians of different shades of opinions will always be divided on party lines. It has worked to the benefit of industry, trade, consumers and has become the single most important tax reform in Independent India. The question, thus, is why can’t this experiment be replicated elsewhere?

Agriculture, rural development and healthcare

Agriculture, rural development and healthcare are areas where, in larger national interest, the GST Council experience heeds to be replicated. Both the Central and the State Governments have several schemes working for the betterment of the farmer. The agricultural sector needs a major support. Both Centre and States spend a large part of their budget in the sector. Similarly, the process of developing rural infrastructure and improving the quality of life in villages has now started. A lot more needs to be done in both agriculture and rural development. Should the Centre and the States be only competing and not supplementing efforts of each other? Should they not be pooling their resources and ensure that no overlap or duplication takes place and that the interest of the largest number is protected and enhanced?

The same is equally true on healthcare. Primary Health Centres, hospitals, health schemes for treatment of poor patients, supply of medicines at an affordable cost are all intended by both Central and the State Governments to ensure that affordable healthcare is available to the people. For those who cannot afford healthcare, it is available at the cost of the Central and some State Governments. Is overlap of expenditure necessary or should it be pooled and spent in an optimum manner?

Are elected Governments intended to non-cooperate with each other or must they work on the principle of “Bahujan Hitay Bahujan Sukhay”. West Bengal, Delhi, Odisha are amongst the States which have refused to implement Ayushman Bharat where every poor family gets upto rupees five lakh of hospitalisation support annually. Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi, Karnataka and West Bengal are non-cooperative in PM Kisan scheme where small and marginal farmers get Rs.6000/- income support annually. Is this in public or national interest? Is it necessary to act against the poor and allow the compulsion of competitive politics to take over?

Society has great faith in the wisdom of men and women. The country hopes that the wisdom prevails over transient political requirements.

Arun Jaitley*

The Exodus Odisha Forgot: Why Lakhs Still Migrate for Survival

The Exodus Odisha Forgot: Why Lakhs Still Migrate for Survival  Over 1.54 billion children and youth are out-of-school. Young refugees, displaced persons and others caught up in conflict or disaster now face even more vulnerability.

Over 1.54 billion children and youth are out-of-school. Young refugees, displaced persons and others caught up in conflict or disaster now face even more vulnerability.  Living In A World Of Uncertainty. COVID-19 may change the world order like never before, People may come out of streets to get two meals a day.

Living In A World Of Uncertainty. COVID-19 may change the world order like never before, People may come out of streets to get two meals a day.  Ill-planned lockdown is leading us to a fatal combination of loss of both life and livelihood – Kamal Haasan writes letter to PM

Ill-planned lockdown is leading us to a fatal combination of loss of both life and livelihood – Kamal Haasan writes letter to PM  Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 in a nutshell

Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 in a nutshell  Kashmir needs a healing touch, radicalization of youth a big challenge!

Kashmir needs a healing touch, radicalization of youth a big challenge!