Will Gita Mehta spearhead Naveen Patnaik’s 2018 dream election vehicle?

INDIA - JANUARY 01: Gita Mehta, Indian writer In New Delhi, India In 1997. (Photo by Robert NICKELSBERG/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

There has been speculation doing around about the possible entry of Odisha Chief MinisterNaveen Patnaik’s plan to bring sister Gita Mehta to counter the rising presence of BJP in the poll bound state of Odisha in 2018. Sources to Odisha Affairs from Delhi reveals that Naveen wants to show a fresh non-political face to the electorate in odisha. Naveen patnaik knows that winning 2018 election will not be a smooth ride as there are growing voices of dissent in the state of odisha given the number of aspirants to contest the election in BJD.

The name of Gita, who shuttles between the US and India, had started doing the rounds in political circles for a Rajya Sabha seat from the state after Naveen had asked Bishnu Charan Das all of a sudden to quit his seat in the Upper House and made him the deputy chairman of the state planning board on March 18.

Rumour mills had been working overtime since the panchayat results were announced in the last week of February, in which the BJD had performed not that well. There were reports that Naveen had been looking for a trusted person to run the party and the government. A section of media speculated about Gita, who had been regularly making quiet visits to Odisha, to spend time with his bachelor brother. Incidentally, they were seen together in public on March 9 when they had visited a book shop in the city to buy books.

A product of the University of Cambridge and author of a number of novels, including the River Sutra, Karma Cola: Marketing the Mystic East and Snakes and Ladders: Glimpses of Modern India, Gita occupies a unique position as a writer, who elucidates uniquely Indian experience in a clear and intelligent voice.

Know Gita Mehta

Nationality: Indian. Born: Gita Patnaik in Delhi, India, 1944. Education: Cambridge University. Career: Writer, journalist, and filmmaker. Lives in New York, London, and Delhi.

PUBLICATIONS

Novels

Raj. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1989.

A River Sutra. New York, N. A. Talese, 1993; excerpt included in Happiness and Discontent. Chicago, Great Books Foundation, 1998.

Other

Karma Cola: Marketing the Mystic East. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1979.

Snakes and Ladders: Glimpses of India. New York, N. A. Talese, 1997.

Gita Mehta is a writer known, perhaps, more for her essays than her novels. She is also a documentary filmmaker and a journalist. These activities all share a focus on India, the country of her birth—its history, politics, and cultures. The same concerns inform her novels: Raj, a historical novel set during the early stages of India’s struggle for independence from Britain, and A River Sutra, a modern revisitation of prevalent traditions of Indian aesthetic and philosophical thought.Mehta has made a number of documentary films about India, covering the Bangladesh war, the Indo-Pakistan war, and the elections in the former Indian princely states. Her essays, as represented by two collections, Karma Cola: Marketing the Mystic East and Snakes and Ladders: Glimpses of Modern India, muse on things Indian, from politics and social unrest, the endless clash of religions and cultures, spirituality, and the Indian textile industry to Indian literature and film, and so on. The style of the essays is personal and lucid, often bitingly clear and always honest. This same lucid immediacy and intimacy marks A River Sutra. Raj, lacking this intimate voice, is a more distanced work, valuable rather for its meticulous and even-handed grasp of a complex and important period in history.

Raj, Mehta’s first novel, begins during the last years of the nineteenth century. The novel’s protagonist, Jaya Singh, is the daughter of the Maharaja and Maharani of Balmer, one of the kingdoms of Royal India. Mehta paints Jaya’s childhood, the traditions and rituals, political pressures and duties that inform her life, with evocative detail. She deals even-handedly with the political and social issues, conveying the immense pain and demoralizing powerlessness with which the Indian people had to deal, while still managing to portray the British with some objectivity. The novel achieves historical sweep, following Jaya from childhood through adolescence to her betrothal and then through her marriage to a Prince of Royal India who has no interest in Indian women, but who, as a Westernized playboy, prefers European women, airplanes, and polo to the duties of a protector of the people. Mehta uses Jaya as a lens through which to view these turbulent years of India’s struggle for independence. She does an admirable job of portraying Jaya’s world—a woman with resources and education raised half in and half out of the traditions of purdah and Hindu ritual that reigned unchanging for generations before her. The novel is rich in detail and complexity. But much of the action, like Gandhi’s salt march or the violent struggles between Hindus and Muslims, is experienced from a distance, through those to whom Jaya is connected rather than through Jaya herself. The novel has been criticized for a lack of character development and depth. Rather than drawing the reader deeply into the unfolding of history, the evenness and limited scope of Mehta’s handling present a somewhat flat aspect, as of great events viewed through the wrong end of a telescope. The novel is most valuable as an account of a lost way of life as it was vanishing within the complex political realities that gave birth, ultimately, to the modern nations of India and Pakistan.

Mehta’s second novel, A River Sutra, is a more intimate and deeply focused work. The narrative centers on India’s holiest river, the Narmada, in the form of a series of tales, or modified sutras of Indian literature. The tales—of various pilgrims to the river—tap the deep veins of Indian mythology and artistic traditions while also forming a prose meditation on the country’s secular-humanist tradition. The character of an unnamed civil servant who has retired from the world to run a government rest house on the river is the thread loosely weaving the stories together—along with the Narmada itself. Mehta’s subject matter here is as rich as the tradition she taps. Classical Sanskrit drama, Hindu mythology, and Sufi poetry all find reflection and reiteration in the novel. One recurring motif playing through the book is that of the raga of Indian classical music. Another is that of Kama, god of love, and the passions and mysteries of the human heart. For all its substance of ancient Indian tradition and thought, A River Sutra is a modern work that acknowledges the difficulties facing modern India at the same time as it takes the reader on a skillfully realized journey into a resonant culture.

Mehta occupies a unique position as a writer who elucidates uniquely Indian experience in a clear and intelligent voice. She relates a rich and ongoing history—its nuance, complexity, and contradiction—opening doors and windows into Indian life in ways few other writers do. While her first novel may be seen as thinly characterized and lacking in depth, the balance of her work, including her second novel, constitutes a unique and valuable contribution to the literature of the world.

Rosetta Hospitality Crowned India’s Crown Jewel in Luxury Hospitality of the Year 2025 at ILC Power Brand Awards

Rosetta Hospitality Crowned India’s Crown Jewel in Luxury Hospitality of the Year 2025 at ILC Power Brand Awards  Network 7 Media Group Announces the 14th Annual India Leadership Conclave & Power Brand Awards 2025 With The Theme: “India@3: Power, Purpose & People”

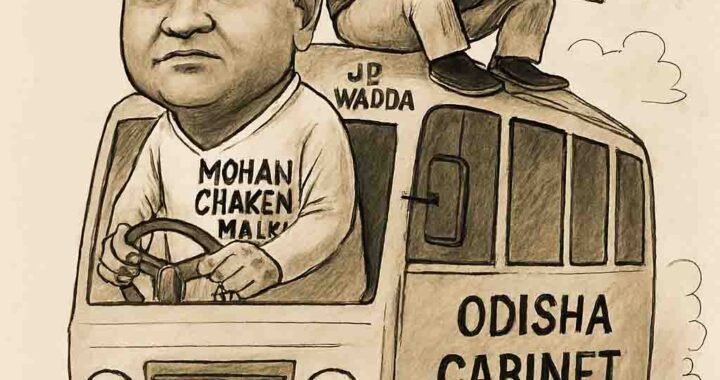

Network 7 Media Group Announces the 14th Annual India Leadership Conclave & Power Brand Awards 2025 With The Theme: “India@3: Power, Purpose & People”  Cabinet Reshuffle Looms as Odisha CM Majhi Meets BJP Top Brass in Delhi

Cabinet Reshuffle Looms as Odisha CM Majhi Meets BJP Top Brass in Delhi  Berhampur’s Fault Lines: Has Dr. Ramesh Chandra Chyau Patnaik Been Cast Out of BJD’s Inner Circle?

Berhampur’s Fault Lines: Has Dr. Ramesh Chandra Chyau Patnaik Been Cast Out of BJD’s Inner Circle?